By Julie Fidler | Natural Society

Nail polishes have been linked to birth defects, thyroid problems, obesity, cancer, and allergic reactions. That’s why many people specifically shop for polishes labeled “non-toxic.” But as past research shows, even nail polishes marketed as non-toxic may contain chemicals that are harmful to your health. [1]

Study co-author Anna Young, a doctoral student at Harvard University, said: [2]

“It’s sort of like playing a game of chemical Whac-A-Mole, where 1 toxic chemical is removed and you end up chasing down the next potentially harmful chemical substituted in.”

It’s not just the nail polish industry that does this; it’s also commonplace in the pesticide and plastics industry.

Supposedly non-toxic nail polishes appeared on the market in the early 2000’s, when many companies began labeling products “3-free.” The phrase signifies that the product is free of:

- Dibutyl phthalate, a plasticizer used to enhance a polish’s texture and function. It has been linked to reproductive and developmental problems.

- Toluene, a known nervous system disruptor.

- Formaldehyde, a carcinogen.

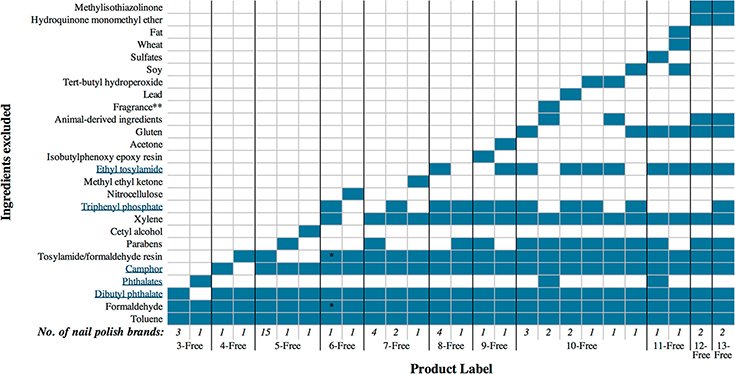

Some nail polish companies took things several steps further by removing even more chemicals, labeling their products “5-free,” “10-free,” and even “13-free.” This, however, does little to educate buyers about which chemicals have been removed and which chemicals have replaced them. That is what Young and her colleagues set out to find.

40 Nail Polishes Tested

For the study, the team purchased and tested the contents of 40 nail polishes from 12 different brands, labeled 3-free all the way up to 13-free.

The study didn’t name the brands, but 2 of the tested brands made up a combined 15% of the nail polish market.

Young said:

“We found that the meaning of these claims isn’t standardized across brands, and there’s no clear information on whether these nail polishes are actually less toxic. Sometimes, when 1 known harmful chemical was removed, the polish instead contained another similar chemical that may be just as toxic.”

Most of the 5-free polishes lacked the same handful of ingredients; however, Young and her team found far less consistency among polishes labeled 10-free and above. The brands varied in how they adhered to the claims on their labels.

None of the samples were found to contain dibutyl phthalate. But polishes with a range of labels tested positive for at least 1 of 2 other plasticizers linked with health problems. One polish was found to contain one of the chemicals its label claimed to exclude.

Just because a nail polish claims to exclude multiple substances, that doesn’t mean it’s safer than one that makes no such claims.

The findings applied to some of the most popular nail polish brands in the industry. Though the samples weren’t representative of the entire nail polish market, Young said the findings are relevant to anyone who likes to add a colorful hue to their nails.

Amusingly, some of the nail polishes the Harvard researchers analyzed excluded ingredients that pose no health risks at all, such as gluten, wheat, fat, and “animal-derived ingredients.” You only have to worry about those if you plan on drinking your nail polish. [1]

It’s not clear how much exposure it takes to affect a person’s health, but nail salon employees, in particular, should be concerned about the potential health risks of their job. [2]

Young said:

“This is especially important for the over 400,000 nail salon workers in the U.S. who could be exposed on a daily basis, for many years, to chemicals that have been linked to health effects on fertility, the reproductive system, fetal development, thyroid function, and possibly even obesity or cancer.”

Young and her fellow authors said that nail polish makers should focus more on excluding entire classes of ingredients – including phthalates and organophosphates – rather than individual compounds. [1]

They wrote:

“Then, certified labels could be useful tools for educating nail polish users, nail salon owners, and nail salon workers about toxic chemicals and how to make best purchasing decisions.”

The study was published in 2018 in the journal Environmental Science and Technology – so hopefully things have changed since then. Either way, be reminded that product labels and claims aren’t always so truthful or accurate.

Sources:

[1] Health

[2] Time

![Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About 9/11 Conspiracy Theory in Under 5 Minutes [VIDEO] | by James Corbett](https://consciouslifenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/911-a-conspiracy-theory-120x86.jpg)