By

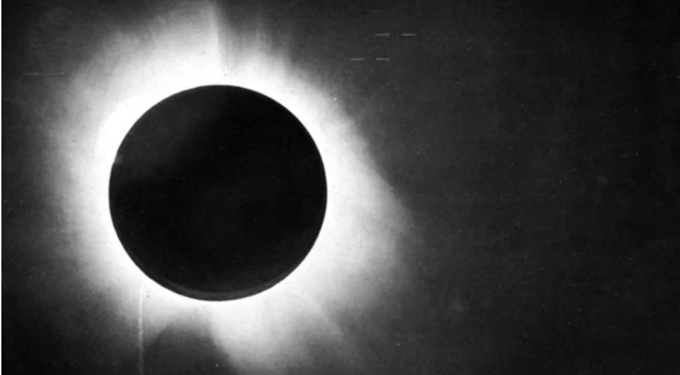

For some skywatchers, the upcoming total solar eclipse on Aug. 21 is more than just a chance to catch a rare sight of the phenomenon in the United States. It's also an opportunity to duplicate one of the most famous experiments of the 20th century, which astrophysicist Arthur Eddington performed in an attempt to prove that light could be bent by gravity, a central tenet of Albert Einstein's theory of general theory.

Amateur astronomer Don Bruns is among those hoping to re-do the experiment. “I thought of it about two years ago. I thought, surely, other people have done it,” he told Live Science. “But no one had done it since 1973,” Bruns said, when a team from the University of Texas went to Mauritania for the solar eclipse on June 30 of that year.

The group ran into technical problems, though, and could not confirm Eddington's results with much accuracy. Other attempts — such as one made for an eclipse on Feb. 25, 1952, in Khartoum by the National Geographic Society — fared somewhat better. [10 Solar Eclipses That Changed Science]

In 1915, Einstein published his theory of general relativity, which states that light will bend around massive objects because space itself becomes curved around such objects. A chance to test the theory came several years later, when a total solar eclipse was set to darken skies on May 29, 1919.

For the 1919 eclipse, Eddington led an expedition to measure the deflection of light from stars near the sun in the sky. Observing from Brazil and Africa, simultaneously, Eddington and his colleagues noted that the position of the stars close to the solar limb differed by a small amount from their catalogued positions, agreeing with the predicted 1.75 arc seconds (or 0.00049 degrees). The announcement that the experiment was a success made Einstein famous.

But later analyses of Eddington's data seemed to suggest that the astrophysicist's confirmation might not have been the slam dunk he thought it was. Bruns said the debate over Eddington's data is why he wants to do the experiment again.

“All these experiments, and the best they could get was maybe 10 percent error,” he said. “I think I can get 2 percent.” Modern instrumentation, as well as more accurate measurements of the positions of the stars, should help refine the measurements needed to replicate Eddington's experiment this time around, he added.

Bruns is taking few chances; he's going to a high-altitude location in Wyoming, where he's likely to have clear skies for the eclipse. And to make sure his telescope's aim is as accurate as it can be, he plans to stabilize his telescope mount by laying down a concrete slab the day before. “We have some quick-set cement,” he said. The slab will also help ensure his mount is absolutely level.

And Bruns is not alone. Richard Berry, the former editor in chief of Astronomy Magazine, will be using his home-built observatory (known as Alpaca Meadows Observatory) to duplicate the Eddington experiment from Lyons, Oregon. [How to Make a Solar Eclipse Viewer (Photos)]

Beyond the sun’s plasma atmosphere, the lensing effect is non-existent. It is therefore not solely the effect of gravity. If they measure lensing at multiple solar radii not just r=1, this will be clearly shown. It is time to rethink relativity. We do not live in a universe dominated by gravity. Electromagnetism is up to 38 orders of magnitude stronger, and linear sources such as cosmic Birkeland currents have much longer range effects than gravitational point sources, with spatial decay the inverse of the square root of distance, versus inverse the square of distance for gravity.