According to a new theoretical experiment, quantum physics indicates that observers witness different histories. Taking this concept to its logical conclusion, this suggests that you and I and others may not necessarily recognize the same historical events–and the very suggestion of such a possibility is sending shock waves through scientific communities who take as a core assumption that there must logically be only one set of true historical facts.

You may have heard that quantum physics has gained a reputation for including such things as, “spooky action at a distance,” and that it somehow involves a cat inside of a box that may or may not be dead–but quantum physics is looking even weirder still, thanks to contributions by theoretical physicists Matthew Leifer and Robert Spekkens, whose work I've been following with great interest, and citing in my published papers, such as Primacy of Quantum Logic in the Natural World.

At the heart of these new observations is the idea that different observers can witness different realities, such that contradictory pictures of reality are observed. This is described in a recent article written by Davide Castelvecchi, Reimagining of Schrodinger's Cat Breaks Quantum Mechanics–and Stumps Physicists.

The headline here is perhaps a bit overly dramatic, as for all practical purposes, quantum mechanics can still be relied upon to deliver consistent results when it comes to it's predictive abilities that we've relied upon for nuclear reactors, and that we are beginning to harness for up-and-coming new quantum computers. What has broken has less to do with the actual physical world breaking as our biased perspective of there being “one and only one historical past.”

The Observer's Role in Determining a Cat's Fate

The original thought experiment designed by Erwin Schrodinger involved placing a cat in a presumedly ludicrous situation where it's fate rests entirely in the hands of a quantum random event, such as a vial of poison gas inside the cat's small room possibly being broken open when the randomizing trigger for the poison vial is activated at a time of decay of a radioactive isotope. What Schrodinger originally found to be an outrageous notion was that, if we were to take quantum physics seriously, the cat inside the box with the poison vial could actually be considered to be BOTH alive AND dead–in a superposition of states–up until the moment when an Observer opened the box to check on the cat. At the moment of such observation, the cat was considered to now actually be either alive or dead, and no longer in the seemingly preposterous state of alive-and-dead.

Introducing a Second Observer

In a small refinement of Erwin Schrodinger's original thought experiment (where no physical cats were actually harmed), Eugene Wigner proposed that we contemplate what would happen when we add to our experimental design of the Observer and the Cat in the box a friend of the original observer. We now have a Cat, an Observer, and a Friend–all waiting to see whether the cat in Schrodinger's box is either alive or dead. And as long as the Observer does not look, we can say the cat can be considered to be in a superposition of states–both alive-and-dead. Once the Observer checks to see what the cat's state actually is, we used to say that we now knew what the outcome is. Yet, another way of viewing this more complex system of observation is that we don't really have a final answer until the Observer's Friend becomes aware of the result.

Complex Systems Can Experience Different Pasts

Complex Systems Can Experience Different Pasts

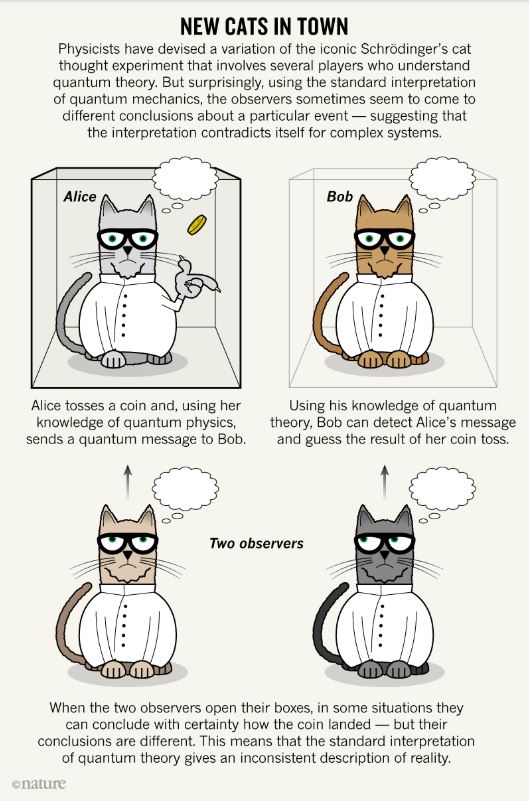

Daniela Frauchiger and Renato Renner of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich shows that “if the standard interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct, then different experimenters can reach opposite conclusions about what the physicist in the box has measured.”

What's new with this thought experiment is the creation of a more sophisticated conceptualization of multiple observers, such that there can now be two Wigner Friends, “Alice” and “Bob,” who are each conducting their own separate observations of a physicist Observer who they keep in a box.

What's interesting about this experimental design is that now when the two Friends open their boxes, they will sometimes make observations that are inconsistent with one another.

While we do not yet have quantum computers available that can prove or disprove the hypothesis that we can expect to see differences in observations in more complex systems of observers, we are moving steadily toward a time when such quantum computers will be able to provide us with a definitive answer on what now appears to be proof of a lack of a singular factual history.

Mandela Effects, Reality Shifts, and Quantum Jumps

There has been a great deal of discussion about this new take on the classic Schrodinger's cat experiment in physics circles, with some of the world's top physicists, such as Stephen Hawking, long ago having already suggested that we may expect to see, for example, physical evidence of there having been many original “big bangs” at the time of the creation of our universe. Hawking co-authored a paper on this topic with Thomas Hertog in 2006, Populating the landscape: A top-down approach.

I suggest this discussion about observers witnessing different possible past ‘truths' and ‘facts' should be very much part of conversation amongst those of us who are noticing such things as Mandela Effects, reality shifts, and quantum jumps. When we recognize that there is scientific precedent for such phenomena, we can hopefully glean insights about the true mysterious workings of Nature, while appreciating our good fortune in sometimes getting to see evidence of such things ourselves.

You can watch the companion video to this blog post at:

___________________________

Cynthia Sue Larson is the best-selling author of six books, including Quantum Jumps. Cynthia has a degree in Physics from UC Berkeley, and discusses consciousness and quantum physics on numerous shows including the History Channel, Gaia TV, Coast to Coast AM, the BBC and One World with Deepak Chopra and on the Living the Quantum Dream show she hosts. You can subscribe to Cynthia’s free monthly ezine at: https://www.RealityShifters.com

Cynthia Sue Larson is the best-selling author of six books, including Quantum Jumps. Cynthia has a degree in Physics from UC Berkeley, and discusses consciousness and quantum physics on numerous shows including the History Channel, Gaia TV, Coast to Coast AM, the BBC and One World with Deepak Chopra and on the Living the Quantum Dream show she hosts. You can subscribe to Cynthia’s free monthly ezine at: https://www.RealityShifters.com